Rajarhat Community Centre: Traditional materials for a modern building

Photo: SchilderScholte architects

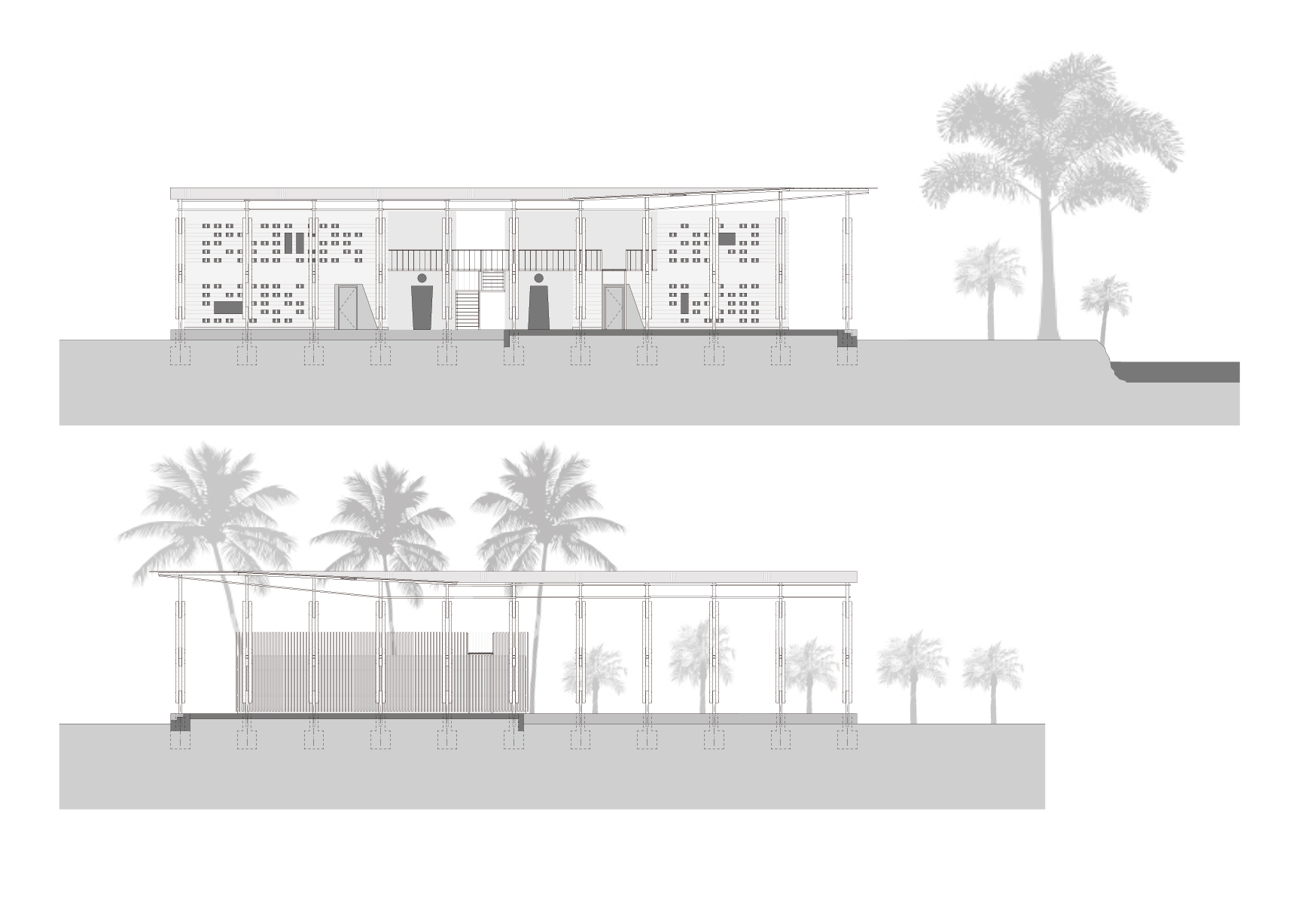

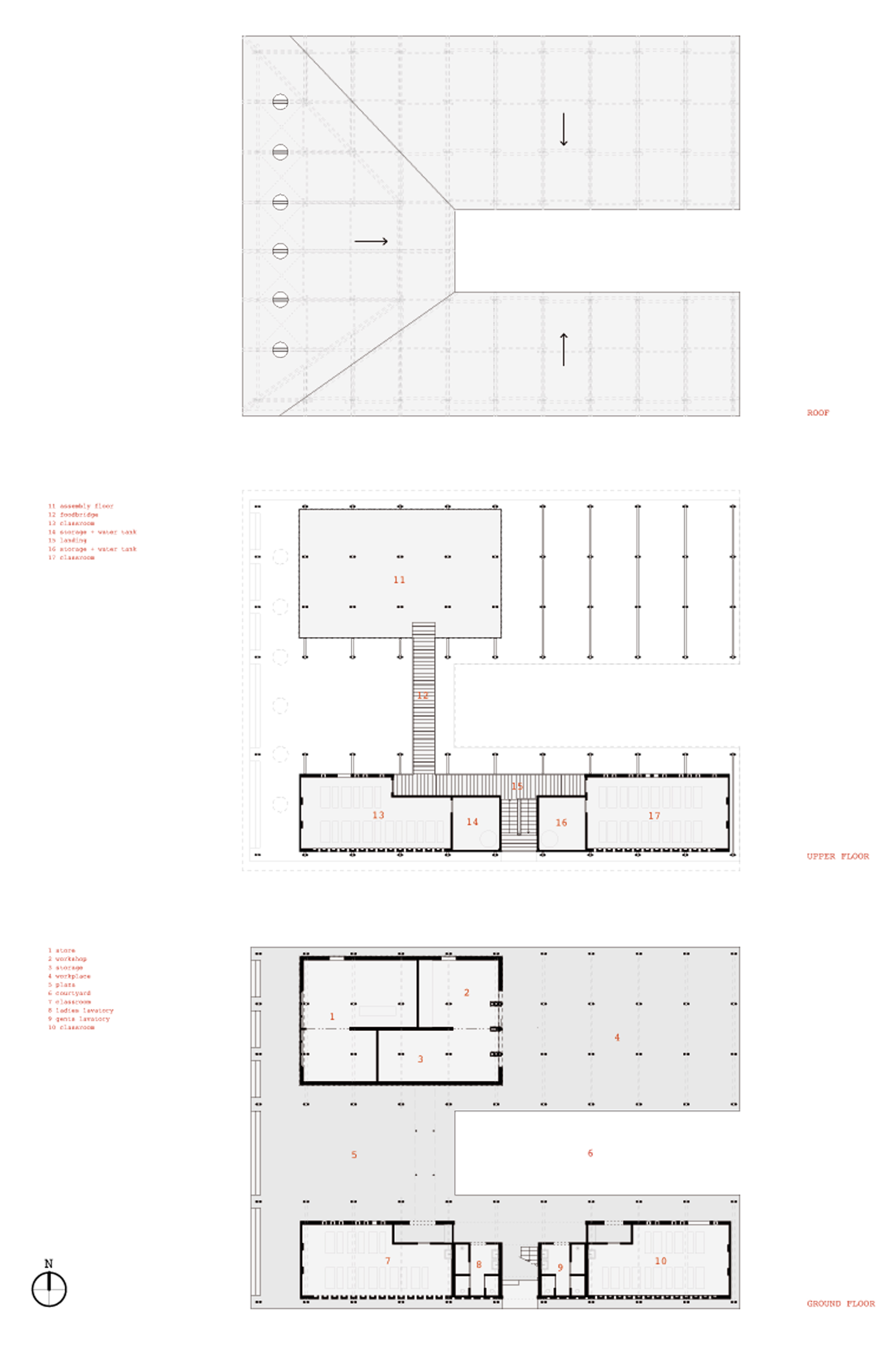

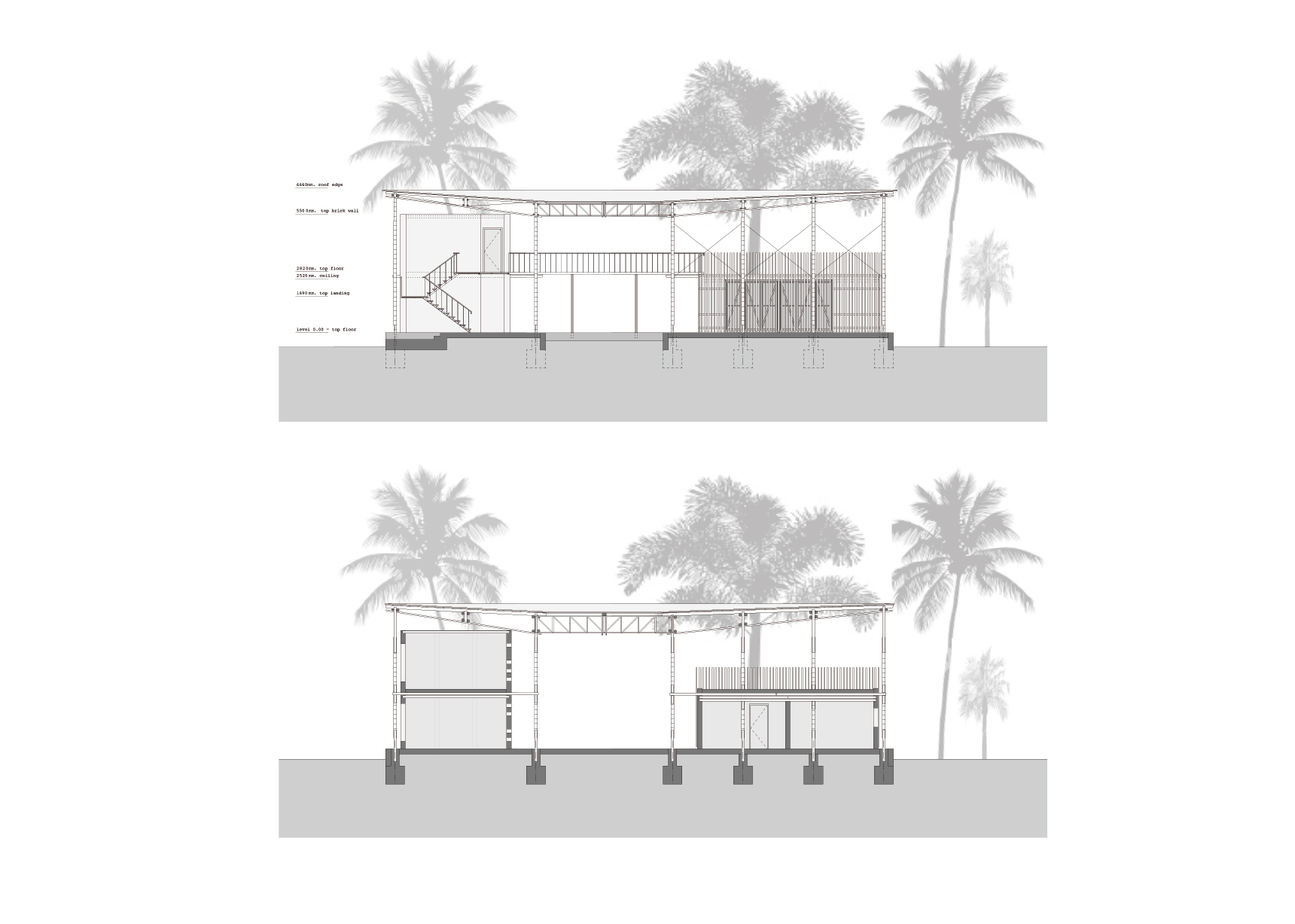

A pond dug out behind the east-west oriented building provides cooling, whereby the luxuriant vegetation also plays a role. The differing materials used at the front of the building, where a road passes by, underscore the centre's dual educational and commercial purpose. Two volumes of differing height stand on a horseshoe-shaped concrete plinth, which clasps a longish, lowered courtyard while also forming a generous entrance area. The bamboo roof structure is supported by a regular grid of columns that follows the U-shaped contour of the plinth, thus allowing air to circulate to prevent heat from building up inside the community centre. The corrugated steel roof juts outwards to the east and west to protect the large openings from rain and provide shade from the sun. On its underside the roof slopes inwards to collect rainwater in the courtyard as a natural source of water.

In the two-storey volume on the southern side of the building, four classrooms provided plenty of daylight are grouped around a double-flight staircase and public toilets as well as rooms for water tanks on the second floor. A single-storey bicycle shop and workshop is located on the northern side, topped by a roof terrace used as an assembly space for public meetings and reached by a filigree footbridge leading from the upper-storey classrooms. The covered interspace at the entrance and in the area behind the workshop is also open to the public and is used as gathering places or for work.

The project pursued the goal of not only bringing together local methods and materials but also of optimising them. Orienting themselves to materials and construction means already in use in Bangladesh, the architects combined brick with corrugated metal panels. The hand-shaped bricks were sourced from within the region and stacked by nearby residents, who also did the rendering on the brickwork walls. This approach reduced costs and, as the methods used were easy to learn, fostered modernisation of regional handicrafts. Bamboo is the main element of the supporting structure and also clads the yellow-painted façade of the bicycle shop, thus referring to the bamboo bicycle frames produced inside. It also minimises use of wood, already a rare resource in the region by any means.

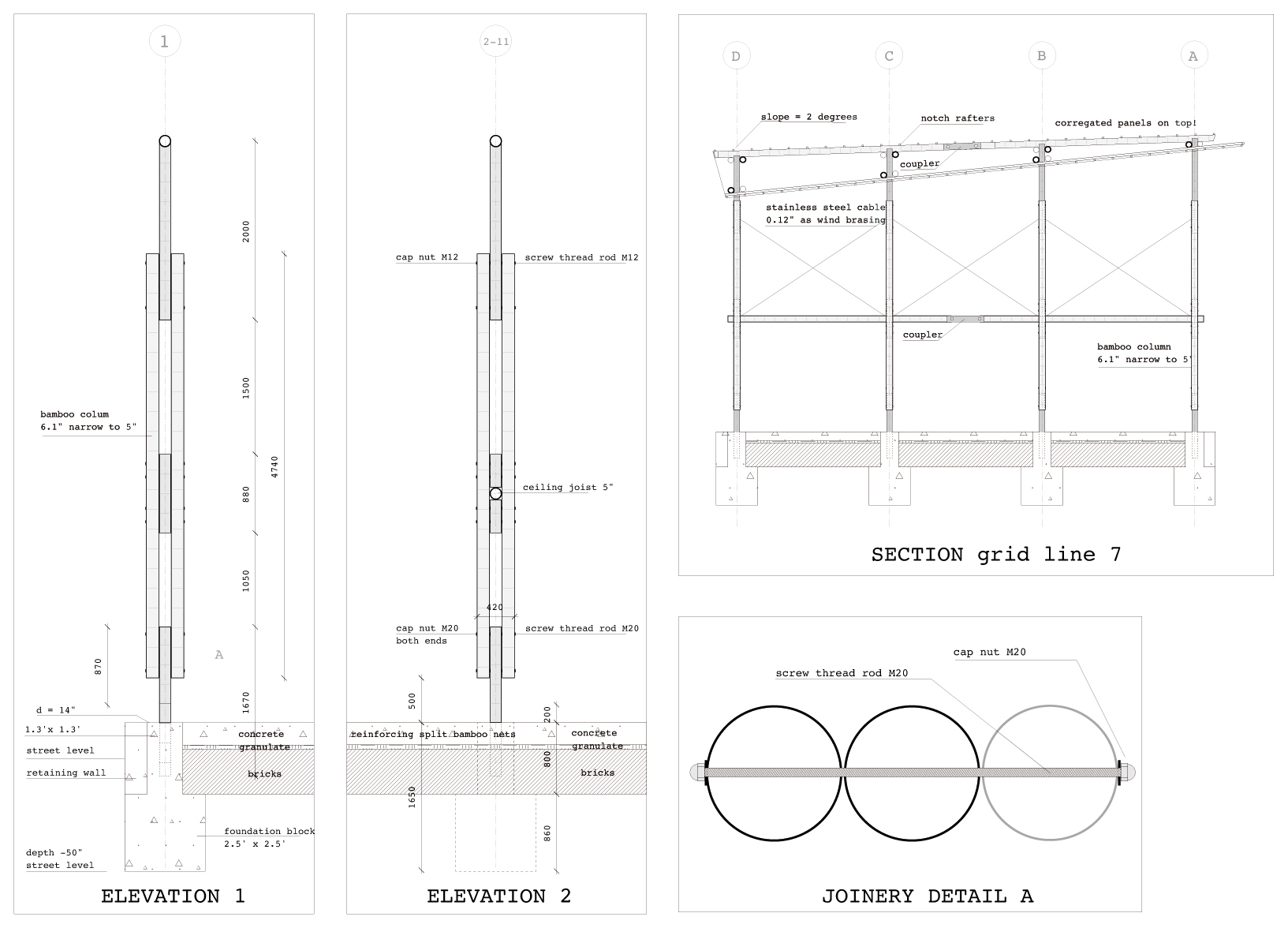

The filigree structure and regular grid of the bamboo columns is simple and also aesthetic. Every column consists of three pieces of bamboo of differing length, with only one of the three touching the floor and the roof. The top piece of cane inserted between the two outer ones serves as the bearing for the transverse beams, which in turn form the roof structure above the two building volumes. When seen face on, the two outer bamboo canes seem self-supporting but are actually screwed to the three shorter pieces. The fenestration of the classrooms recalls the vertical gaps between the bamboo that clads part of the building.

The pragmatic colour scheme chosen for the community centre is friendly and welcoming in effect. The predominant colour is yellow in reference to the flowers of the mustard plant found all over the country, and is also used in the window reveals to ward off insects. The pale blue of the classrooms keeps flies away, while the other shades in the scheme, namely grey and black, recall the colour of Bengal earth before and after rainfall.

The noteworthy community centre by SchilderScholte Architects in Rajarhat shows that it is possible to use conventional local resources to create unconventional ecological architecture.