Water, fire, earth and air: Architecture faculty in Kigali

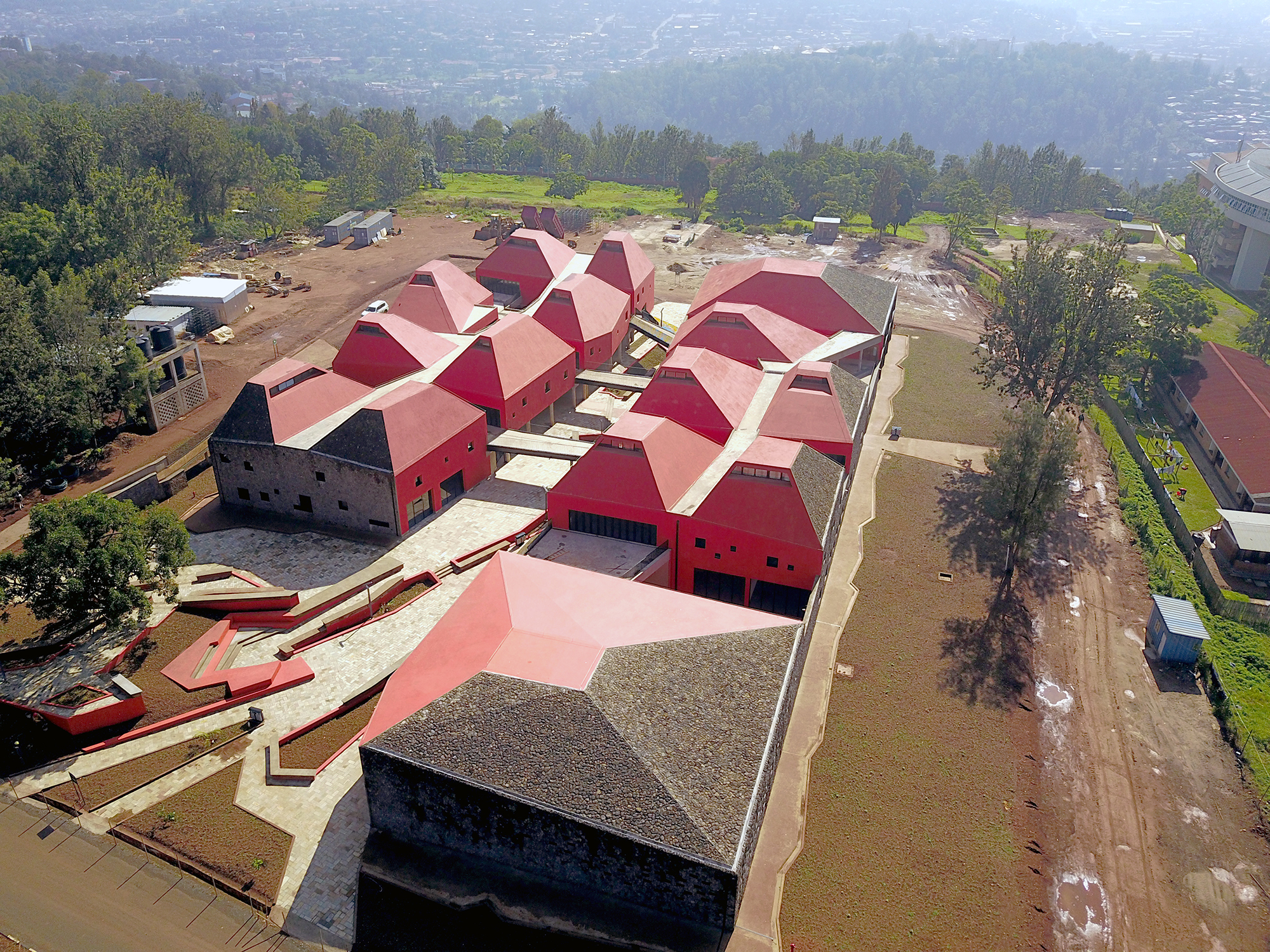

Foto: Faed Jules Toulet

Architectural education is still in its infancy in many parts of Africa. Important prerequisites for changing this state of affairs have been created in Rwanda, a country once torn by civil war and now sometimes referred to as "the Switzerland of Africa" due to its economic strength and landlocked location. Today, the College of Science and Technology at the University of Rwanda has gained a new architecture faculty, 20 years after the college's foundation. An international competition for the design was won in 2012 by Patrick Schweitzer & Associés of Strasbourg, with their building complex being completed on high ground west of the capital Kigali in late 2017.

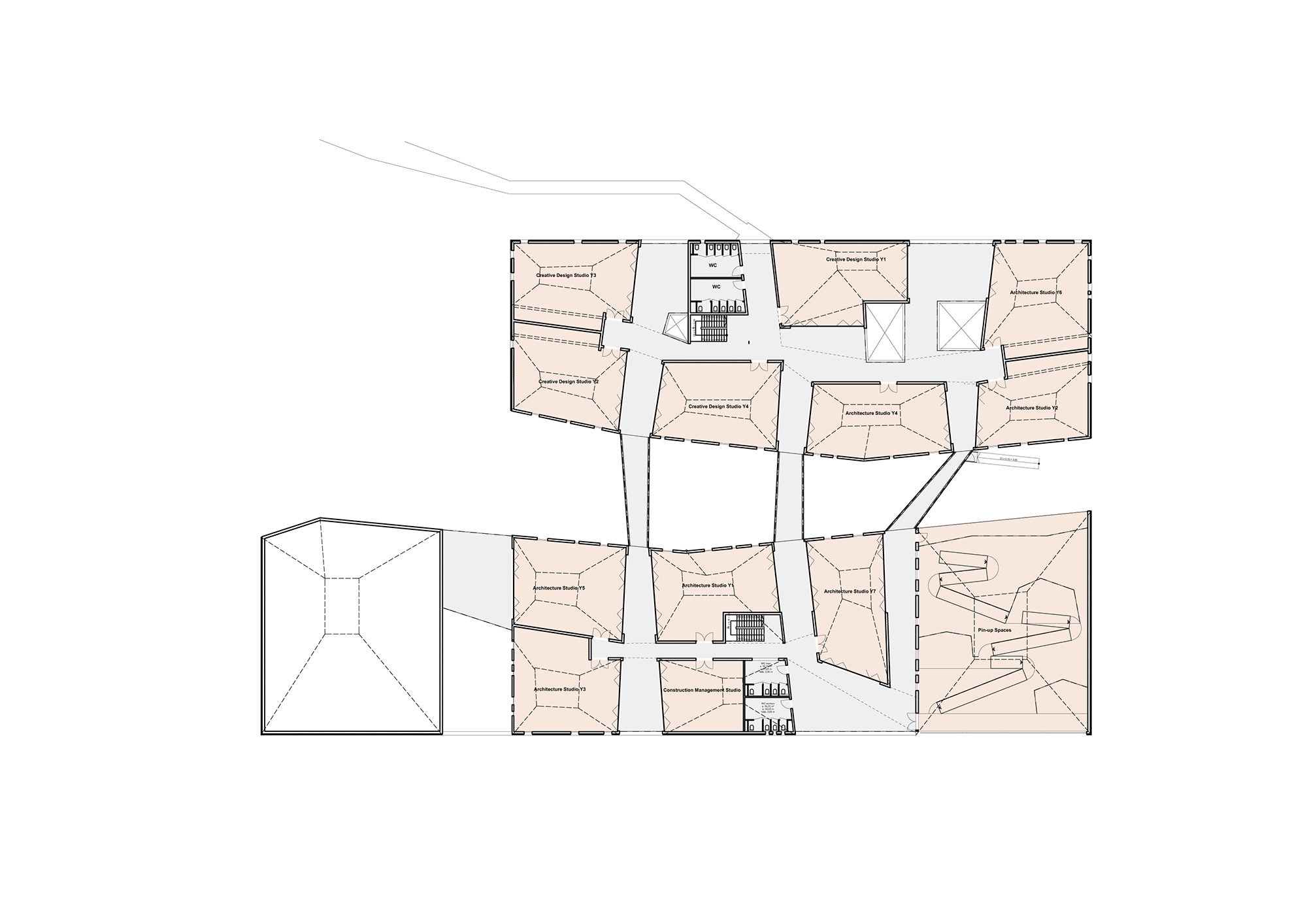

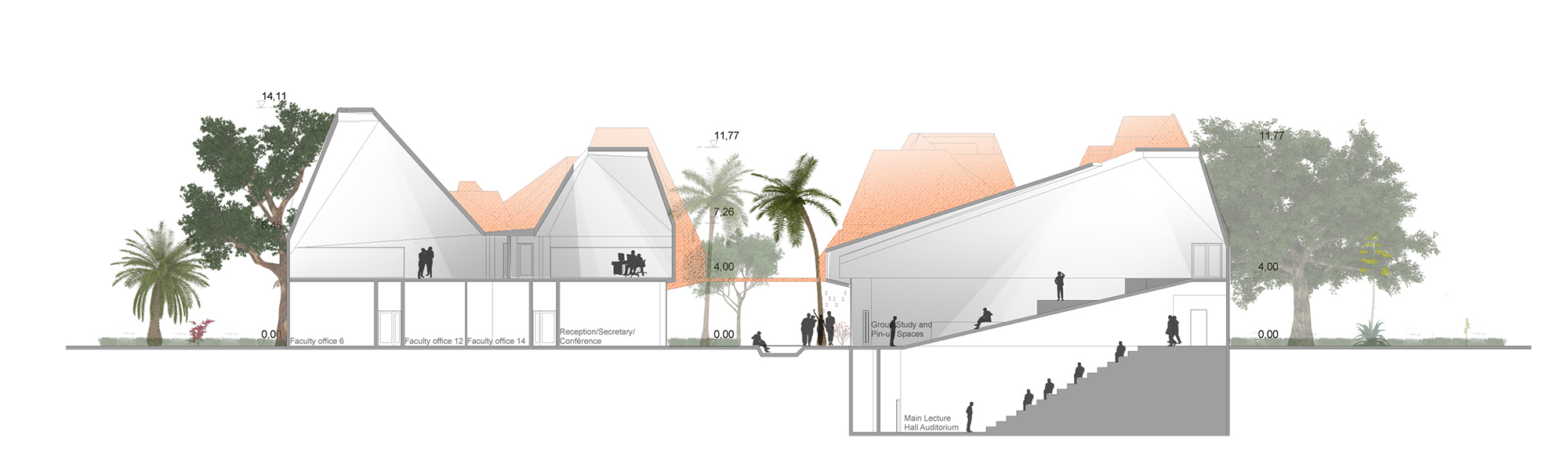

Instead of designing a compact block, the architects came up with a village-like building complex compartmentalised into small, merely two-storey units strung out along a central circulation axis. Offices, workshops, computer and seminar rooms as well as a large lecture theatre are located on the ground floor; studios for the students and a largish room for discussing designs have been placed on the upper storey. The new 5,600-square-metre complex with its 13 striking pyramid-shaped roofs has space for 600 students altogether.

In their choice of materials the architects took their inspiration from the four elements of fire, water, earth and air from Ancient Greek philosophy. Concrete walls clad in lava rock standing for the element of earth close the faculty off to the outside; at the same time, the building complex opens up to the central circulation axis as far as the local climate allows. Openings in the facades and high up in the concrete roofs foster the circulation of air – the second element – with the result that the buildings manage to do completely without mechanical heating or cooling systems. The element of fire is symbolised by plaster painted bright red on the roofs and the insulated concrete facades. Finally, the planting beds in the open spaces stand for the element of water, with roof runoff not flowing away into the sewage system but into cisterns.

Numerous footbridges form links between the individual volumes at the upper floor level. The architects dispensed with an elevator for cost and maintenance reasons; rather, a long ramp provides barrier-free access to the upper storey and meanders through the design discussion hall.

Benches and seating steps in the open spaces with their varied design are to foster communication among the students and in some cases are produced out of rammed earth. Elsewhere again the architects went to some lengths to enable incorporation of local handcraft traditions in the project wherever possible, to the extent that a carpentry and metal-working workshop was especially set up on the grounds during the construction phase. The walls and ceilings of the units were made of site-placed concrete in the traditional way and in places clad with lava rock set in a mortar bed. Up to 400 persons altogether simultaneously found employment at the building site.

Instead of designing a compact block, the architects came up with a village-like building complex compartmentalised into small, merely two-storey units strung out along a central circulation axis. Offices, workshops, computer and seminar rooms as well as a large lecture theatre are located on the ground floor; studios for the students and a largish room for discussing designs have been placed on the upper storey. The new 5,600-square-metre complex with its 13 striking pyramid-shaped roofs has space for 600 students altogether.

In their choice of materials the architects took their inspiration from the four elements of fire, water, earth and air from Ancient Greek philosophy. Concrete walls clad in lava rock standing for the element of earth close the faculty off to the outside; at the same time, the building complex opens up to the central circulation axis as far as the local climate allows. Openings in the facades and high up in the concrete roofs foster the circulation of air – the second element – with the result that the buildings manage to do completely without mechanical heating or cooling systems. The element of fire is symbolised by plaster painted bright red on the roofs and the insulated concrete facades. Finally, the planting beds in the open spaces stand for the element of water, with roof runoff not flowing away into the sewage system but into cisterns.

Numerous footbridges form links between the individual volumes at the upper floor level. The architects dispensed with an elevator for cost and maintenance reasons; rather, a long ramp provides barrier-free access to the upper storey and meanders through the design discussion hall.

Benches and seating steps in the open spaces with their varied design are to foster communication among the students and in some cases are produced out of rammed earth. Elsewhere again the architects went to some lengths to enable incorporation of local handcraft traditions in the project wherever possible, to the extent that a carpentry and metal-working workshop was especially set up on the grounds during the construction phase. The walls and ceilings of the units were made of site-placed concrete in the traditional way and in places clad with lava rock set in a mortar bed. Up to 400 persons altogether simultaneously found employment at the building site.

Further information:

Engineers: Egis, Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines

Landscape architects: Acte 2 Paysage, Obernai

Contracting business: CATIC

Landscape architects: Acte 2 Paysage, Obernai

Contracting business: CATIC