Architecture Biennale 2025 in Venice

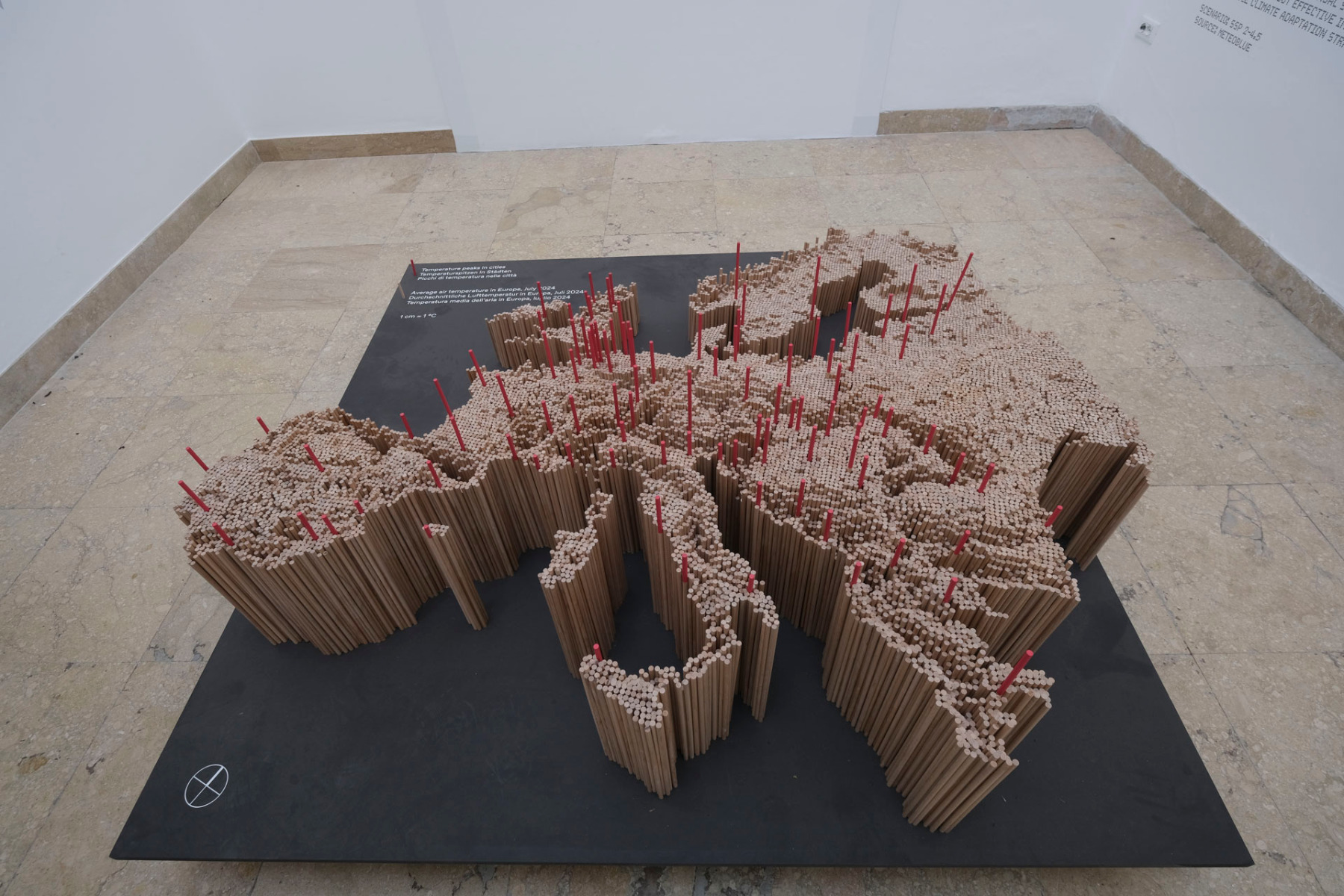

What Helps to Combat the Heat in Cities?

The contribution “Heatwave” in the Bahrain pavilion was awarded the Biennale's Golden Lion for the best national contribution. © Jakob Schoof

The hot season in Venice has only just begun. In the summer months, an oppressive sultriness settles over the lagoon city, accompanied by the smell of stagnant water in the canals. The many tourists who descend on Venice in the summer endure the heat without complaining. At this year's Architecture Biennale, however, urban warming has become a central theme.

“Terms and Conditions” by Transsolar as a prelude to the main exhibition, © Jakob Schoof

Impressive start to the main exhibition

Right in the first room of the Arsenale, curator Carlo Ratti makes the drama of the situation palpable: dozens of air conditioning units fill the darkened room with their waste heat. Bathed in an unreal light from an electric arc, their image is reflected in shallow pools of water. The installation by Stuttgart-based Transsolar is a start with aplomb. The subsequent exhibition leaves many viewers rather perplexed. This is mainly due to the weighting of the exhibits: material experiments and AI fantasies play the central role in the rooms. Genuinely architectural solutions to the world's problems, on the other hand, are relegated to the margins.

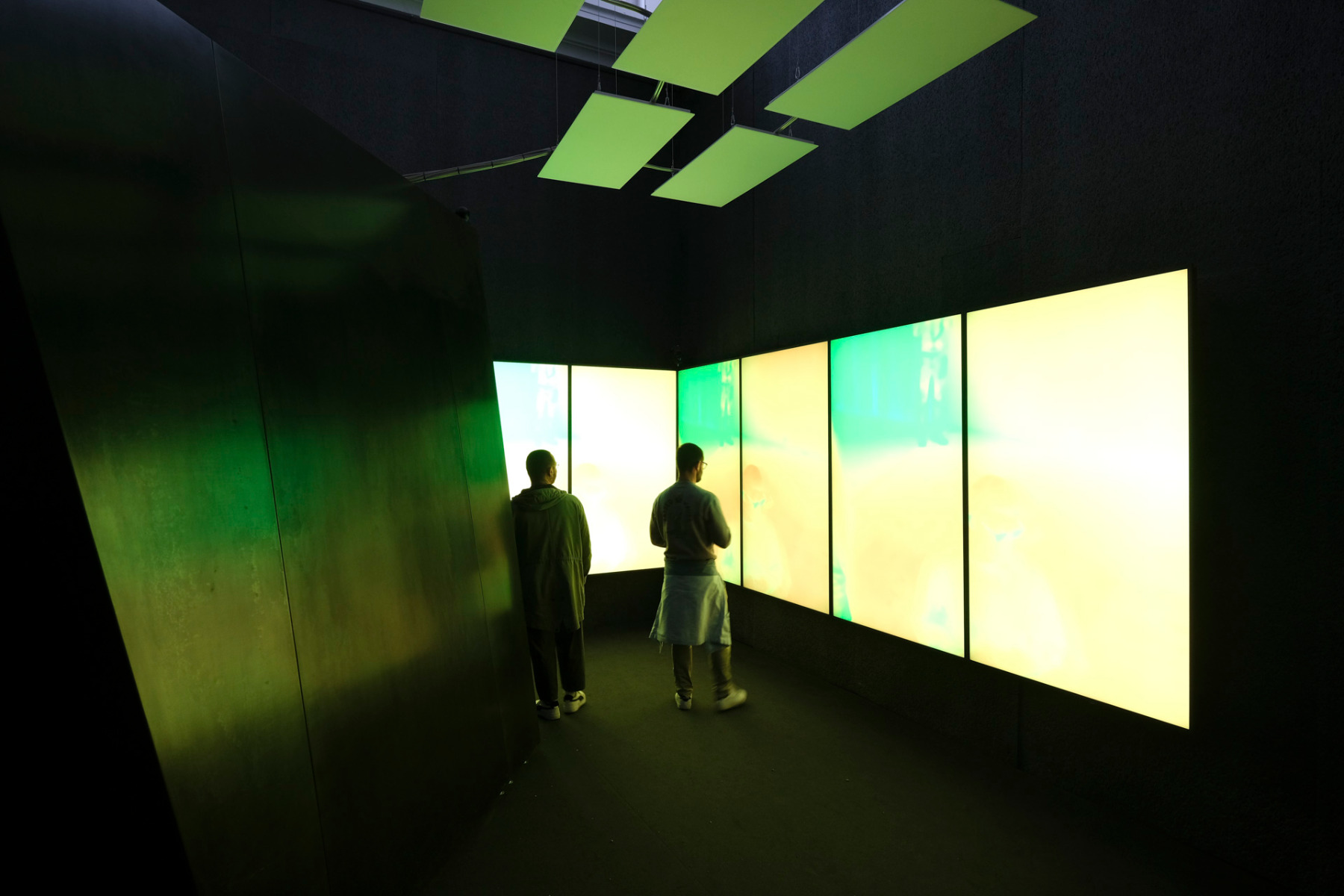

“Stress test” in the German pavilion. Curators: Elisabeth Endress, Gabriele Kiefer, Nicola Borgmann, Daniele Santucci. © Jakob Schoof

Spaces to feel in the German pavilion

Urban warming cannot be described in words – you have to feel it. The four-member curatorial team of the German pavilion also adhered to this credo. Under the motto “Stress Test”, they divided the mirror-symmetrical pavilion into two halves: On the right, visitors are exposed to the stress of the heat; on the left, they can relax in a fresh breeze under trees. In the large entrance room in between, room-filling video projections illustrate the topic of urban warming. They juxtapose thermal images of urban spaces, examples of climate-friendly construction and the common architectural production of concrete, asphalt and sealed surfaces. Two further rooms provide statistics on soil sealing and heat waves in cities and explain possible solutions. Cities need more shade, more trees, more green spaces and not just the odd high-maintenance green facade as a consolation. Conclusion: The message has been received, but in other pavilions the same theme has been staged in a more impressive way.

“Keep cool” at the Salone Verde. Installation by the University of Stuttgart, the HfT Stuttgart and the TH Deggendorf. Curators: Martin Ostermann, Diane Ziegler, Sabine Wiesend. © Jakob Schoof

Textile shade providers in the Salone Verde

There are many places in Venice where you can see how to respond to urban heat stress. In the Salone Verde, one of the many off-locations outside the Biennale grounds, two Stuttgart universities and the Deggendorf Institute of Technology are approaching the topic in an artistic way: One of the two exhibition rooms contains a filigree net structure, fitted with shade providers made of mushroom mycelium. In the room opposite, carpets hang from the historic ceiling beams, slightly blown by the artificial wind from the fans. Obviously, urban cooling is not possible without mechanical support. It would have been nice to test the actual performance of the shade providers directly – why they are hung in the interior instead of in the spacious courtyard of the Salone Verde will remain the curators' secret.

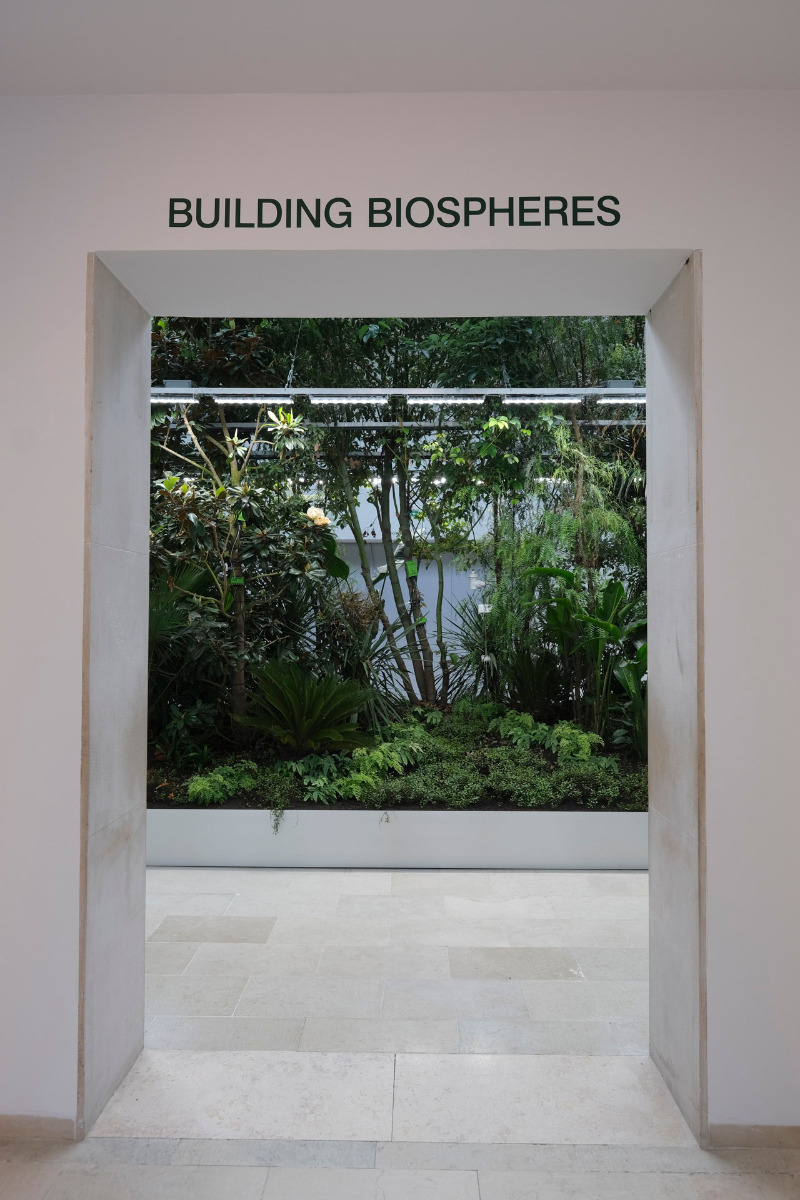

“Building Biospheres” in the Belgian pavilion. Curators: Bas Smets, Stefano Mancuso. © Jakob Schoof

Plants as a tool for indoor cooling

Bas Smets and Stefano Mancuso, on the other hand, have opted for their very own kind of urban greening. Their contribution “Building Biospheres” in the Belgian pavilion deliberately ignores the recreational value of green spaces and uses plants primarily as a tool. With their help alone, Smets and Mancuso want to create a constantly mild indoor climate in buildings that requires neither heating nor cooling. On closer inspection, the immense amount of technology required to achieve this becomes clear: In the exhibition pavilion, the nutrient and heat balance of the vegetation is constantly monitored. In addition, buildings would have to be constructed in a completely different way than before in order to control indoor humidity. In the next room, experimental designs for the renovation of two buildings in Brussels are on display. They also make this clear: To ensure lush, climate-effective plant growth indoors, buildings require elaborate ventilation, irrigation and dehumidification systems. In other words, the exact opposite of “building simply”.

“Urban Evaporative Cooling and the Ecological Semiotics of Heat and Pollution in Athens”. Project team: Jon Goodbun, Aran Chadwich, Flora McLean, Rosa Schiano-Phan, Juan Valledo. © Andrea Avezzù

© Andrea Avezzù

Low-tech evaporation screens in Athens

It may help to look beyond Central Europe to find simple but functional methods of urban cooling. In a park in Athens, John Goodbun from the Royal College of Art in London and his team have erected several 7-metre-high cooling towers that work using evaporation. According to their own information, a temperature drop of 10 °C was measured within 15 minutes. In the coming years, the team plans to repeat the temporary installation with towers ranging from 5 to 30 m to find the optimum height. Their contribution can already be seen in the main exhibition at the Arsenale in Venice.

“Make it Rain” in the French pavilion. Project team: Quentin Gérard, Elisabeth Terrisse de Botton, Matthieu Brasebin, Guillaume Deman. © Quentin Gerard

Pouring allowed in Brussels and Logroño

The “Make it Rain” installations, which a Belgian team led by architect Quentin Gérard has realized in several European cities, also operate with evaporation. The basis of the whole thing is a covered bench made of fired bricks. Users have to do the watering themselves. In the installation in Brussels, rainwater is collected in a tank and pours over the bricks when a tap is opened. In Logroño, Spain, the team cooperated with a kayak club. Here, river water is collected in a tank and can then be distributed over the stones using small watering cans - a playful, low-tech approach to the issue of urban warming.

“Heatwave” in the Bahrain pavilion. Curator: Andrea Faraguna. © Andrea Avezzù

Cooling ceilings for public spaces

The desert state of Bahrain presented the most impressive and certainly the most expensive method to combat urban heating in its pavilion – and rightly won the Golden Lion for the best national contribution. The team of curators led by Andrea Faraguna presented the functional prototype of a cooling ceiling for public spaces. The system uses the coldness of the earth or seawater and the fact that the ground temperature in the Gulf below 15 m is 27°C all year round. According to calculations by Alexander Puzrin, Professor of Geotechnics at ETH Zurich, a 20 m deep geothermal probe is capable of cooling 200 liters of air per second from 47°C to a comfortable 32°C. Structurally, the systems can be adapted to specific situations and can be used in very different ways: As a market hall, schoolyard or parking lot canopy or as heat protection over traffic junctions. The installation would also be suitable for Venice: After the end of the Biennale, the curatorial team is aiming for a permanent location with seawater cooling in the lagoon city, for example in the marina on the island of San Giorgio Maggiore.

Exhibition: 19. Biennale Architettura 2025

Exhibition venue: Venice (IT)

Exhibition duration: 10th of May until 23th of November 2025

Opening hours: daily except Monday, 11 am - 7 pm

Further Information: labiennale.org